I emailed him and asked some questions about the body of work, and he was kind enough to answer.

Andy Duncan: How long have you been working on this project, and do you think there will ever be an "end" to it, or point at which it will be considered finished?

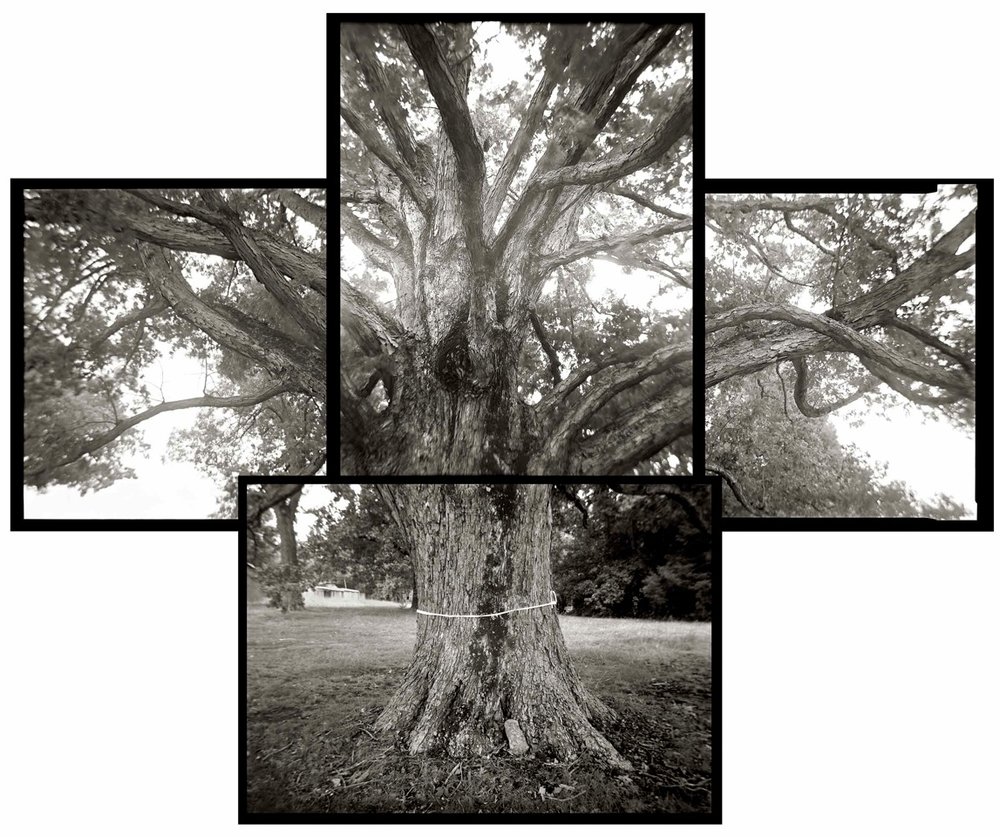

David Shannon-Lier: I have been working on this project for a little over 5 years now, though the first year and a half to two years of that was spent figuring out how to make the pictures and refining my methodology. I hope to put a book of this work together and I am actually working on including long exposures of the movement of the sun. This is a little trickier as days tend to be a bit windier than nights. I am now building a folding wind break to bring with me on my trips after this last outing.

AD: What was your inspiration for this work?

DS-L: The inspiration for the work came when I was driving from Massachusetts to Arizona for graduate school. I began to think about our old home and how as we drove west it was slowly setting below the horizon. It occurred to me that I rarely thing about the larger world in three dimensions. I wanted to make work that would point to that gap in our thinking. Now I see that gap as a metaphor for the gap in our conception of our own lives: we know we are small, ephemeral beings, but we can't shake the notion that the things we do every day carry some sort of weight.

AD: How did it begin, and how has it evolved?

DS-L: The work began as mostly technical problems and solutions. How to plot the motion of heavenly bodies? How to do it accurately enough to where the pictures didn't fall apart? How to nail down the exposure, especially considering small apertures and reciprocity failure? These problems took the better part of a year an a half, most of the experiments taking place in my back yard. As I solved those problems, I began to travel in concentric circles around our home in Arizona, at which point I had to solve other problems to do with travel and how to do this out of a car and away from the support of a home base. Now all that is behind me, which makes the work easier, but in some ways less exciting in the execution. The concepts have developed a bit and I now see the work as about that particularly vexing mix we have as a species of being mortal, conscious and aware that we are both.

AD: Do you have any thoughts or ideas of what comes next for your photography?

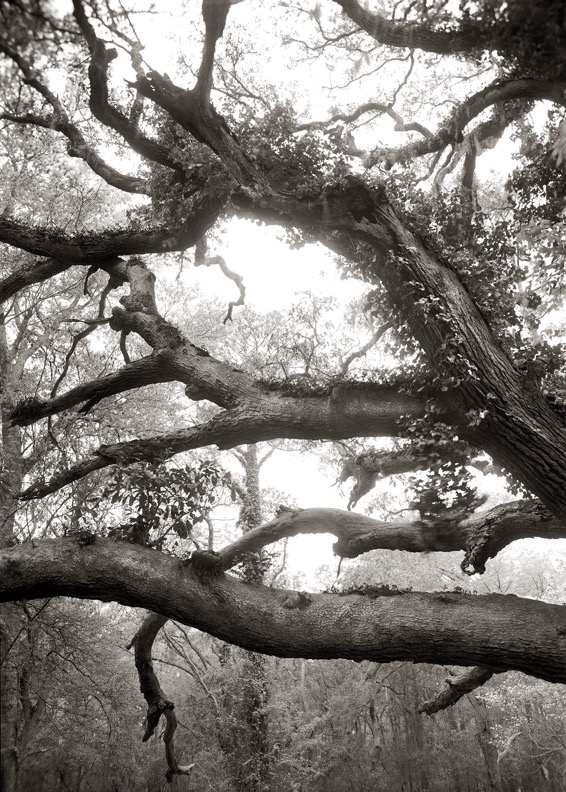

DS-L: I am always taking pictures of things that fascinate me. I am interested in the landscape and the sublime, particularly that aspect of the sublime that is closest to fear or dread. It seems to me in these moments we can begin to get at that human knot I mentioned above.

AD: Who is a favorite photographer of yours?

DS-L: There are a lot. I find the best persona to embody as a visual artist is a compulsive thief. It does no good to steal from one artist or movement, or even one medium. But if you can constantly be taking in new information, and stealing a bit from here, a bit from there, from other artists as well as science, philosophy, theology, culture the work will end up being rather more interesting. This is all to say that sometimes (as is the case with compulsive thieves) I am unaware that I am borrowing from some area until long after and I could spend entirely too long listing all of them. All that being said I will mention Bill Burke and Mark Klett, who I worked closely with and who have influenced me by osmosis. Also, someone who is working now and really gets at the ideas of the landscape and the sublime is Michael Lundgren.

AD: Because I'm a bit of a tech junkie, what programs or software do you use to project or predict the positioning of the sun and the moon?

DS-L: The solution to that technical problem was to use very accurate data and a very accurate tool for measuring the data. I started getting my data from the U.S. Naval Observatory, but I now use an app called stellarium. It has the same data, but is a little easier to access on the road. From that I can get the precise location for any heavenly body at present or in the future. I use a surveyor's tool called a transit, or a theodolite to plot the points that I get from the data, and then place my camera in the spot where the transit made its measurements. It's a bit more complicated than that and a lot more tedious, but that's the gist of it.

Man, I loved the part about stealing from everywhere! I've heard the quote that's often attributed to Pablo Picasso: "good artists borrow, great artists steal." But for all the times I've heard it, I never really thought to apply the stealing to all facets of life, not just to steal from other artists.

Thanks for your time David! I can't wait to see more of your work!

To see more of Lier's work, which I highly recommend, you can visit his website. Also, he's been featured on LensCulture, Fraction Magazine, and Hoctok.