This one is for the photo historians/family historians/found photograph enthusiasts. Rebecca Sexton Larson's work has a foot in just about every aspect of the medium of photography, as well as other artistic media. Rebecca uses pinhole cameras, the bromoil process, salt prints, found photographs (which she alters), digital negatives, and hand-painting techniques to create images that range from whimsical, to surreal, to sublime.

Carol Panaro-Smith & James Hajicek

I've long been an admirer of and influenced by the work of collaborative duo James Hajicek and Carol Panaro-Smith. I discovered their photogenic drawing work around 2004-2005 when I was really getting into making Lumen prints.

Their work hearkens back to, and indeed is directly born from William Henry Fox Talbot, the originator of photogenic drawings, the experiments for which began in 1834. He discovered that paper coated with a salt solution, then brushed with silver nitrate turned black when exposed to light, and a final coat of salt halted that darkening. He then made what is essentially a photogram, placing botanical specimens on the sensitized paper, and exposing it to sunlight. Thus, the "photogenic drawing," and one of the first successful photographic processes was born.

Today, James and Carol use variations of Talbot’s early formulas, and create beautiful pieces that are layered, possess depth, and have fantastic textures. I remember being stunned at the colors and textures the first time I saw their work, and those same feelings return each time I look at their work.

Earth Vegetation 08/17

Their compositions are so simple and organic, as if they clamped the plants between the glass and paper right where the plants grew out of the dirt.

Earth Vegetation 06/01

A paragraph, and specifically the last half of it, of their artist statement for their latest body of work, Arc of Departure, resonates in me, and describes the experience of making this sort of work so much better than I’ve been able to in the past:

“The work evolved in stages from its initial intellectual underpinnings through a focus on the physicality of the remaining organic artifact to the spirituality of experiencing “the awe” of being in the immediate presence of this sacred transformative act - magic in its very essence, ruled by serendipity, elusive mysteries, fugitive images, and the ruling master of all – the ultimate impermanence of everything.”

Arc of Departure 09/09

Be sure to visit their website, and you can read an article about their work on Lenscratch. It’s well worth it to spend some time with their work, which can be seen at the Joseph Bellows Gallery, the photo-eye Gallery, and the Tilt Gallery.

Carleton Watkins (American, 1829 - 1916)

[Piwayac - Vernal Fall - 300 ft. Yo Semite], 1861, Albumen silver print

40.2 × 52.1 cm (15 13/16 × 20 1/2 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Carleton Watkins

Carleton Watkins (American, 1829 - 1916)

El Capitan, 3600 ft., Yo Semite, negative 1861; print about 1866, Albumen silver print

39.1 × 51.3 cm (15 3/8 × 20 3/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

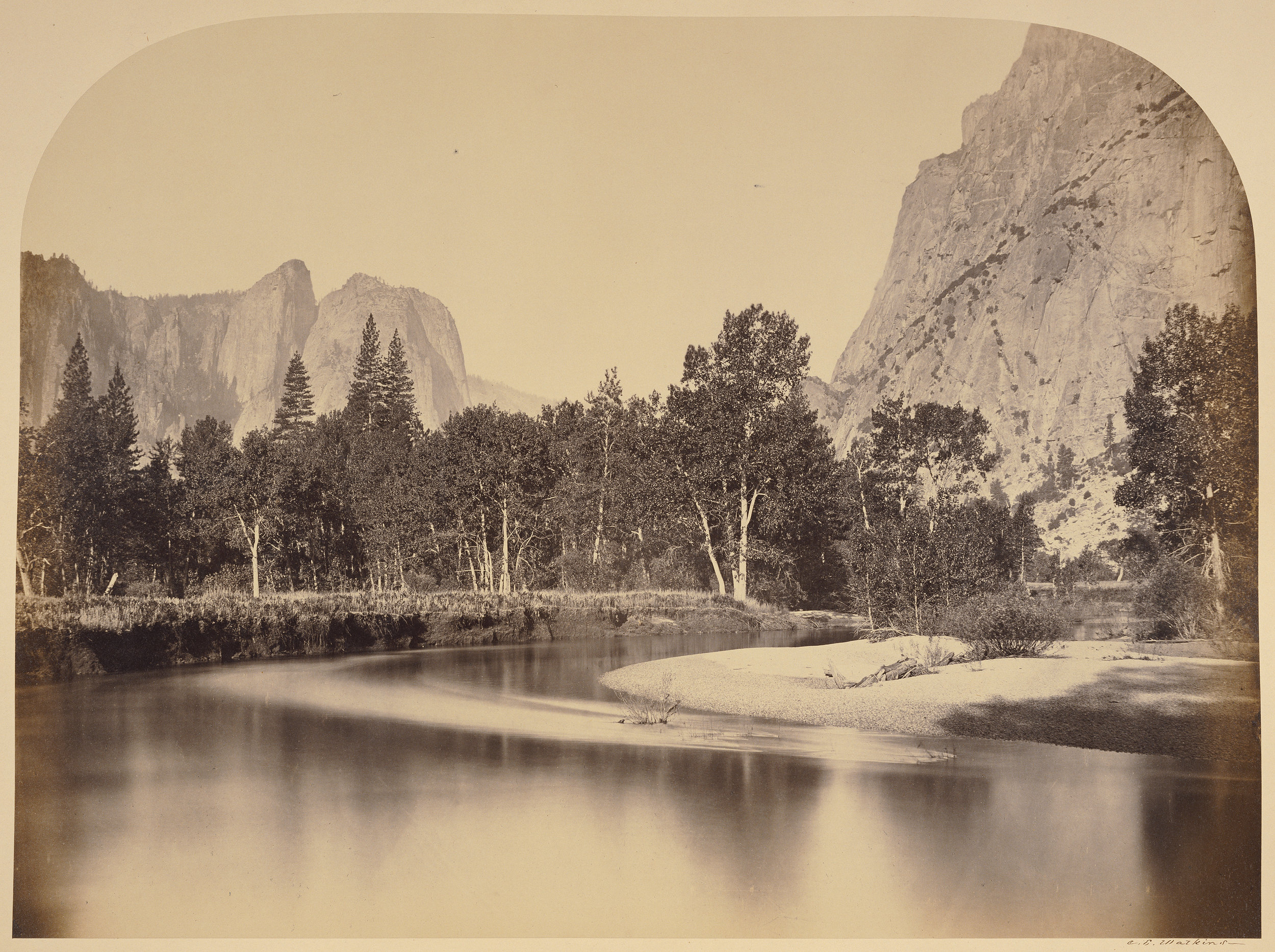

Carleton Watkins (American, 1829 - 1916)

View from Camp Grove down the Valley - Yo Semite, 1861, Albumen silver print

39.1 × 52.5 cm (15 3/8 × 20 11/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

[Stream with trees and mountains in background, Yosemite Valley, Calif.]

Carleton Watkins (American, 1829 - 1916)

[The Devil's Slide, Utah], 1873 - 1874, Albumen silver print

52.1 × 39.1 cm (20 1/2 × 15 3/8 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

https://www.carletonwatkins.org/

Eadweard Muybridge

After last month's post on Timothy O'Sullivan, I thought it might be fun to make that a pattern, and talk about some of my influences each month.

Eadweard Muybridge didn't immediately become one of my influences. I think in my History of Photography class we mainly discussed his motion studies and experimentation. But I could be wrong; I was in Seattle for half of that semester while I was prepared to donate bone marrow to my brother who was undergoing treatment for Leukemia. It wasn't until about three years after that class that I really began paying attention to his landscape work he did in Yosemite.

Today, Muybridge is most known for his motion studies, which began with him being hired to settle a bet between two men, one of whom was Leland Stanford. The bet was whether a horse, when galloping had all four hooves off the ground, or if an animal that size was always in contact with the ground. Muybridge was hired, and devised a system of 12 cameras set at intervals along a race track, which was all in white. A trip wire was attached to each camera so that when the horse passed in front of it, the shutter was tripped and the exposure was made. This was in the days of wet plate collodion, when exposures were seconds long, so it really is remarkable for Muybridge to have figured out how to reduce the exposure time enough to stop motion the way he did. This led him to perform many more studies of animals and humans in motion. These studies ultimately led to the invention of the motion picture.

Though most known for the motion studies, Muybridge started out his professional photographic career as a landscape and architectural photographer. He photographed San Francisco, and surrounding areas including Yosemite. Some of the scenes he photographed in Yosemite were made from the same point as photographs made by his contemporary and competitor, Carleton Watkins.

For an excellent biography on Muybridge, read Rebecca Solnit's book River of Shadows: Eadweard Muybridge and the Technological Wild West

Or if you don't want to buy a book, you can read this excellent bio over at Imaging-Resource.

Or you can just check out the Wikipedia article on Muybridge.

Timothy O'Sullivan

This week, I thought I'd dig back into photography's past and look at one of my all time favorite photographers. Ansel Adams was my first influence as a photographer, but he was soon supplanted by Timothy O'Sullivan, Matthew Brady, Edward Muybridge, Carleton Watkins, and others (now that I've chosen to do a post on O'Sullivan, I'll likely do posts on the other afore mentioned photographers). I still remember thumbing through my History of Photography text book back in college at the beginning of the semester, and seeing the photograph below and thinking something along the lines of “Ah, an Ansel Adams photograph” and then looking at the caption and learning that it was actually made by O’Sullivan.

After that, I dug a little deeper into O’Sullivan’s work. I don’t really remember my initial impressions, or how soon afterwards he became one of my favorite photographers. And I’m not really sure there is a photograph of his that I would call my favorite. I think what impressed me first about O’Sullivan, and the other 19th Century landscape photographers was the incredible effort that was put into making their photographs. I loved imagining myself alongside them, a portable darkroom pulled behind a horse with hundreds of pounds of glass plates, hoping they don’t break along the journey, rushing to make an exposure before the collodion dried.

O'Sullivan started his photographic career as a Civil War photographer, apprenticed under Matthew Brady, then after the war worked as the photographer for several Survey Expeditions in the West.

I’ve always found the choices O’Sullivan made to be intriguing. He never made the obvious choice when making his compositions, even when working during the Civil War. He had a sensitivity to the landscape that I still envy.

You can read more about O'Sullivan and view more of his work at the Smithsonian American Art Museum's website.

![Carleton Watkins (American, 1829 - 1916) [Piwayac - Vernal Fall - 300 ft. Yo Semite], 1861, Albumen silver print 40.2 × 52.1 cm (15 13/16 × 20 1/2 in.) The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/51a57431e4b07c0410ab2d9e/1551561412652-S2CPABKZKM39Q1AS9NRQ/CW06216601.jpg)

![[Stream with trees and mountains in background, Yosemite Valley, Calif.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/51a57431e4b07c0410ab2d9e/1551561495641-6MAL0QYQAIGXQCFYXXSM/CW08117v.jpg)

![Carleton Watkins (American, 1829 - 1916) [The Devil's Slide, Utah], 1873 - 1874, Albumen silver print 52.1 × 39.1 cm (20 1/2 × 15 3/8 in.) The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/51a57431e4b07c0410ab2d9e/1551561527807-9PRUO8RRC6YBQU5JBPQS/CW06210801.jpg)